|

thóg sé tamall orthu ... an sorcas tagtha go Raithean |

they were a long time coming . . . the circus arrives in Rahan |

|

長いお成りだ・・・ サーカスが着く ラハンによ Leagan Seapáinise: Mariko Sumikura |

they wur a lang time cumin... the circus wins in till Rahan Leagan Béarla na hAlban: John McDonald |

2022-02-28

Fr Francis Browne

2022-02-27

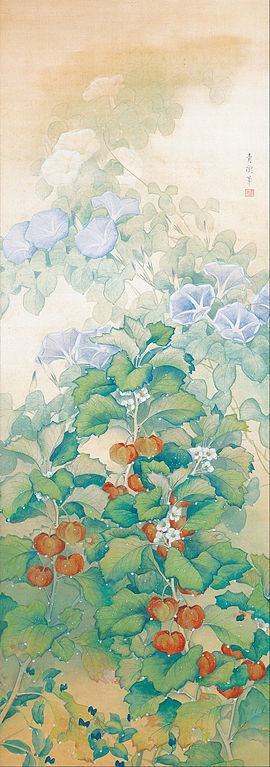

朝露 - 小茂田青樹

|

brief glimpse of a former life - morning dew |

|

spléachadh gearr ar shaol roimhe seo - drúcht na maidine |

|

前世の 短き顕現― 朝露に Leagan Seapáinise: Mariko Sumikura |

|

juist a glisk o a bygane life - mornin deow Leagan Béarla na hAlban: John McDonald |

2022-02-26

Hashimoto Kansetsu

|

giobún ambaist! ceolfhoireann dofheicthe á stiúradh aige i gcónaí |

ah, the gibbon! always conducting an invisible orchestra |

|

手長猿 いつも指揮振る 見えぬ楽団(オケ) Leagan Seapáinise: Mariko Sumikura |

ah, the puggie! aye conduckin an unveesible orchestrae Leagan Béarla na hAlban: John McDonald |

2022-02-25

Shaku Choku

ikite ware |

d'fhágas slán acu |

Tanka (5-7-5-7-7 siolla) de chuid Shaku Choku (1887 - 1953)

2022-02-24

Muinéal / Neck

Sa saol seo

(N'fheadar faoin saol eile)

is gá muinéal a bheith agat

in this world

(whatever about the next)

you need to have

a bit of neck

2022-02-23

Tigh i gCearnóg Chonnacht / A House in Connaught Square

who said: "Well, I don't really careabout Lenin or Marx'cause when my doggie barksyou can hear him all round Connaught Square!"

2022-02-22

Մարտիրոս Սարյան (Martiros Sarian)

2022-02-21

The Cemetery, Étaples

| |||

|

fead ón dtraein ach níl freagairt ó na mairbh - Reilig Étaples |

a train whistles but the dead do not respond - Étaples Cemetery | ||

|

汽笛呼べど 死者応えずに― エタプル墓地よ Leagan Seapáinise Mariko Sumikura |

a train fussles bit the deid tak nae heed - Étaples Cemetery Leagan Béarla na hAlban: John McDonald | ||

2022-02-20

Ludovic Allaume

feictear thú gach lá nó feictear uair amháin thú nó ní fheictear thú feictear thú i do Mhaighdean nó tagann siad ort i ndán |

|

some see You daily others once in a lifetime some never see You some find You in the Virgin others find You in a poem |

2022-02-19

Roger de La Fresnaye

|

scrios an Bastille seo oscail geataí mo chroíse saor na príosúnaigh cimí darbh ainm an t-éad an dúil is an t-éadóchas |

|

it is Bastille Day open the gates of my heart free the prisoners they are legion: jealousy desire and sheer hopelessness |

2022-02-18

I gcuimhne ar Thomás Mac Siomóin

Athfhoilsiú ar aiste a scríobhadh cheana maidir le saothar Thomáis, a cailleadh inné.

What is the Irish problem? I’m sure the Irish have many of the same problems as everyone else on earth,maybe more, maybe less. So what exactly is the Irish problem we are addressing here?

There’s a clue in the name itself, Irish. You see, the Irish don’t speak Irish! Not anymore. Less than 10% of the population. A lot less! Why is this? Well,there are lots of reasons.

In his book The Broken Harp, Tomás Mac Síomóin outlined a grim scenario when describing the fall and decline of the Gaelic world and the terrible effects of colonialism on the Irish psyche. Ghoulish, nightmarish actually, the stuff of monster movies, zombie movies.(More on that presently).

And there’s been a cover up. And the cover up continues. And we have to ask ourselves, why can’t we clean out the closet once and for all and breathe freely again. Put all those ghosts to rest, jabbering away in Irish, English, Kiltartanese, Cant and whatever you’re having yourself.

Mac Síomóin has followed The Broken Harp with another book, more conversational in style, The Gael Becomes Irish (2020).

Who is Mac Síomóin? He could be described as an Irish cultural exile who has lived in Catalonia for over 20 years. Writer. Journalist. Marxist. Scientist. Poet. Contrarian, according to his detractors. One could say that the Gaelic form of his name is in itself a statement, as most of the surnames and place names of Ireland are known by their Anglicised form, which often lends an air of idiocy to them, whether intended or not.

There’s the nub, already. The Irish have accepted Anglicisation and only a dedicated few wear a badge of resistance; one such badge is using the native form of one’s name and address. Using the native form of one’s name doesn’t necessarily mean you can speak, write or read Irish, however. That’s part of the Irish problem too. And vice versa! Some of the best Irish speakers I have heard never used anything but the English form of their name.

Many native speakers of Irish in Gaeltacht areas (Irish-speaking) are known by the English form of their names, or avoid the problem of the surname altogether by becoming known under a string of Irish-sounding and English-sounding Christian names, such as Paddy Mháire Dick, which places one on a recognisable family tree. Others have a name that distinguishes them in some manner or other, such as Máire an Bhéarla, meaning ‘Mary who can speak English.’ Maybe weshould all have that suffix attached to our names!

VANQUISHED ANCESTRAL UNIVERSE

English legislation regarding Anglicisation of names was not uniformly enforced and, so, you sometimes have the added complication of having people of the same family using different forms of their names: O’Houlihan and Holland, for instance. Houston, we have a problem!

But actually, it’s not funny. It’s serious. It’s symptomatic of a widespread disease, a sickness, a virus . . . the virus of colonialism. As Mac Síomóin says,

‘References that reflect his vanquished ancestral universe are replaced by those of the coloniser’s civilisation. The linguistically colonised becomes part of the referential universe of the coloniser.’

This is undoubtedly true. I remember reading a Sunday newspaper, in hospital, (which I normally avoid like the plague, i.e, hospitals and that particular rag!) The newspaper alluded to didn’t contribute to my rehabilitation, I can tell you that much. Au contraire. What attracted my eye (or what appalled it, I should say) was the crossword. It was oozing withwhat Mac Síomóin calls, above, ‘the referential universe of the coloniser’. Yes, there I was in a hospital bed, and an ‘Irish’ newspaper was worming its way into my mind with vile crossword clues regarding British royalty, British celebs and other questionable forms of life. Three across, four down . . . some bugger or other who was awarded the Victoria Cross. Help! Nurse!

COMPLETE CULTURAL COLONISATION

How do we allow ourselves to be treated in this insidious manner? The answer is simple. Mac Síomóin has got it right:

‘Linguistic colonialization is complete cultural colonisation.’

The Colonial Effect is not some superficial veneer, a silly hat, or bonnet, that we can wear and take off at will, a sly peep at the Chelsea Flower Show, or even the Graham Norton Show, God forbid. No. Mac Síomóin insists otherwise: we are powerless! We’re stuck in the mire.

‘Colonialism has sunk such deep roots in our psyche that a need to restore the riches that were taken from us no longer has any relevancy for the majority of our fellow citizens.’

This is a hard-hitting analysis of the Irish problem, but a necessary one. Whenever it comes up, it is swept under the carpet, or derided. Being mealy mouthed about the subject would not serve any purpose at all. And Mac Síomóin is right to be riled about all of this. In a sense, it’s a matter of life and death because if the Irish language joins the list of those languages that have been dying at a rate of one per fortnight in recent decades, no one is going to turn up for the funeral – out of unspoken shame.

The crossword maker whose Anglocentric ravings upset me in hospital would probably not last very long with that particular newspaper if his research reflected the mores, insights, proverbs, songs, oral and literary culture of Irish, a language which stretches back over three thousand years. No, he’d be out on his ear. So would the literary editor, if he or she decided tomorrow to devote space every Sunday to reviews of Irish language books.

You would think that someone who makes crosswords for an Irish newspaper – or a literary editor for that matter – would be interested in Irish words, their history and etymology. But no, it’s as though his mind has been washed clean of our Gaelic past and the known universe is now merrily filtered through an Anglophone prism.

Mac Síomóin’s book reproduces part of an interview with the wonderful Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o who describes language as a natural computer, a natural hard drive.

‘When you lose that hard drive,’ says the great African writer and intellectual, ‘you lose all thememories and knowledge and information andthoughts carried by that language . . .’

What a frightening prospect! It has something of thequality of a sci-fi film script, doesn’t it? Losing all that referential material, and in exchange for what? Make no mistake about it. There’s nothing sci-fi about all of this. It is real. It has happened. It continues to happen and we allow it to continue because we have not woken up to the fact that we are being manipulated left, right and centre. F****d sideways.

TRAUMA AND LANGUAGE LOSS

The trauma associated with language loss is described in Mac Síomóin’s previous title, The Broken Harp, and some of that deeply disturbing material is recapitulated here again. Why not? We need to know what happened and why it happened. Our educators and teachers also need to know what happened, and why and how it happened, and we need to unveil to Irish schoolchildren, once and for all, and unfold the bloody tapestry of the history of Ireland’s senior language. How on earth can the rising generation acquire a language at school, even the basics, if they don’t know its long and chequered history? What do you suggest,that it be taught in a vacuum?

We seem to be living in an anodyne society in which it is impolite to step on another’s toe, whatever shape or colour that particular toe might have, whatever its sexual predilections and so on! So, in that light, your average teacher in Ireland is unlikely to quote as follows from Mac Síomóin’s book:

‘The catastrophic Irish military defeat at Kinsale in 1603, and the subsequente migration to the continent of its civic and military leaders, initiated the gradual incorporation – aided by several genocidal interludes – throughout more than three succeeding centuries, of the Irish nation into English cultural and administrative practise. Such a process, plus itsfundamental economic aspect, is referred to as colonisation . . .’

Genocidal interludes? Has the Irish educational system the mind, or the heart, or the guts to talk about such things? If it did, wouldn’t there be complaints, letters to the newspapers and so on? Whatever about our teachers, and parents, have our children got an appetite for such things? (Or are their appetites too dulled by violent video games?)

Aren’t we all living in an age of appeasement now, a golden age of fraternal relations with our brothers and sisters on our neighbouring island? Why open upall those old sores? Why re-arrange the chieftain’s bones, as Patrick Kavanagh asked.

POETS HUNTED DOWN

We’re not finished yet. Mac Síomóin continues relentlessly. In this violent game, there’s only going to be one winner, and one loser:

‘Public use of the Irish language was penalised, except where practical considerations made its complete elimination impossible; it was all but completely eliminated from administrative affairs at a time when the native Irish population knew no other language. Poets and popular entertainers were hunted down and their works and musical instruments, when discovered, were destroyed.’

Great stuff! Why don’t they make a violent video game out of that? Hey, wouldn’t that be fun! What will we call this game? I know, Broken Harps! I love it! Let’s go hunting down some poets. Come on! Let’s smash some harps. First to smash 20 harps wins! Why stop there! There’s loads more to come. You ain’t heard nothing yet. It just gets better and better:

‘All non-Anglican religious practise was prescribed.[recte proscribed]. Roman Catholics, the vastmajority of the population, along with UlsterPresbyterians, were subject to Penal Laws, designed to impoverish them and keep them illiterate. Catholic priests who received their training in continental seminaries, were hunted down; rewards were offered for their head . . .’

THE OAK IS FELLED

Can you visualise it? Another computer game! Hunting priests. Hang them high! It could go viral! Well priests aren’t very popular today so it doesn’t matter. As long as those nasty Brits didn’t touch our trees. They didn’t touch our trees, did they?!

‘The oak forests which covered Ireland, in which most of our ancestors lived, and from which their fighters emerged to attack their English occupiers, were systematically felled. The wood both fed the furnaces of early industrial England and was used to construct the ships of England’s naval fleets.’

Ah yes, Rule Britannia!

| ||

| The Slave Ship | J.M.W. Turner |

So, Tomás Mac Síomóin, I’ve known you and listened to you for over 40 years: maybe your polemics will bear fruit some day soon and we’ll have a slew of new video games to beat the band. Who needs dragons and what not when such genuine, colourful violence lies at our very own doorstep. Rich pickings, I say. Perhaps it’s happening already. We’ve had the film of the ‘Great Hunger’, Black 47 and now, more recently, Arracht. After all, entertainment is the linguafranca of the hour and arracht means ‘monster’ so it must be monstrously good:

As may be obvious, I go along with Mac Síomóin’s thesis is most respects but I would like to conclude by mentioning three areas where we part company. Firstly, his view of contemporary Irish-language literature is unnecessarily bleak.

I think it was ungracious of him not to mention – even in a footnote– the remarkable energy and diversity of the Irish language IMRAM literature festival, a festival which honoured his own achievements not so long ago. True, many of its events are poorly attended – even stalwarts of the Irish-language movement fail to turnup! Members of the wider arts community also fail to make an appearance, even out of curiosity (unless they are part of an event).

Aha! Yes, but this is part of a larger malaise, as the ever-percipient John Zerzan notes in the current issue – pre-Covid-19 Lockdown – of Fifth Estate: Clubs are closing as people retreat further into their little screens. When people go out, they are so very likely to be at their tables on their phones. We do less socialising, have fewer friends . . . More and more is delivered to one’s door … Everything is available online, even cars:

Maybe IMRAM needs to do a rethink and bring some of its events to us for a while, rather than having a couple of hundred people venturing out into the real world and attending actual events!

I won’t be watching any IMRAM events on a smartphone simply because I don’t have one: I have a computer screen, yes, but I don’t want to witness the diminution of life, or art, on a small screen. I don’t want to ‘watch’ music, or view Turner’s The Slave Ship on any little gadget. It’s the leprechaunisation of everybody and everything.

Secondly, I differ with Mac Síomóin when he recommends simplifying the Irish language as taught in schools. Try simplifying chess. Or hurling. Why would you even think of such a thing!

Finally, Mac Síomóin advertises his book by saying that

‘international considerations increasingly determine our national cultural parameters’.

Sure. Nobody can argue with that. But the author is a Marxist and, by implication, a statist. We would have had a different book from him had he been an anarchist, a book which would have identified the state itself (whether the British state, the neo-colonial Irish state, or some possible European super-state of the future) as a major part of the Irish problem.

2022-02-17

Tanuki

Faigh réidh leis an gcac

cinnte ... ach deimhnigh

nach dtuirlingeoidh sé ar éinne

get rid of your waste matter

by all means... but make sure

it doesn't land on someone

2022-02-16

Of Men and War

|

an gliaire lomnocht is é ag fáil bháis athuair nach mór an spórt é is spéis le cách an chogaíocht thar dheora goirt' na máthar |

|

the gladiator - dying all over again for our amusement our strange appetite for war no one heeds the mothers' tears |

Of Men and War is a tanka in Irish and English (5-7-5-7-7 syllables) in response to a photograph by Eugène Atget taken in 1923. After the Great War, Atget photographed a lot of mannequins and statues, including this replica of the Dying Gladiator. From the torque around his neck, we know that he was a Gaul, or Celt.

2022-02-15

Vasily Vereschagin

|

féach cad a dheinis – tá fakir déanta agat díom cleasaí gan chleasa mé i mo staic, a thaisce ní fios cad atá ionam |

|

look what you have done – changed me into a fakir one who has no tricks i just stand there, Belovèd people wonder what I am |

|

κοίτα τι έκανες - με έκανες φακίρη έναν χωρίς τρικ απλώς είμαι, Αγάπη τι να 'μαι, όλοι λένε Sarah Thilykou a dhein an leagan Gréigise |

2022-02-14

Elizabeth Butler

|

| Study of a British Soldier with Two Camels, Camel Corps, Egypt, 1st Sudan War |

bródúil as a bpáirt

in Arm na Breataine -camaill is dreancaidí

proud to servein the British Army -camels and their fleas

2022-02-13

Wakayama Bokusui

|

iku san ka koesari yukaba wabishisa-no hatenamu kuni zo kyo mo tabi yuku |

|

an mó sliabh is abhainn atá curtha díom agam is arís inniu ag fánaíocht liom go huaigneach tríd an gcríoch seo gan teorainn |

Tanka (5-7-5-7-7 siolla) de chuid Wakayama Bokusui (1885 - 1928)

2022-02-12

Ferdinand Hodler

| ||

|

táim im’ Iób agaibh mallacht ar mo chairde gaoil is ar Rí na nDúl an fada a bheidh sibh dom’ chrá is dom’ bhascadh le focail? | ||

|

i have become Job i curse my fate and my friends curse the Almighty how long will ye vex my soul break me in pieces with words? |

2022-02-11

Haiku Búdaíocha : Stanford M. Forrester

halla machnaimh . . .

|

| Stanford M. Forrester |

mo chumas cruinnithe meabhrach

sciobtha ag seangán

solas na camhaoire . . .

na búdaí cloch go léir

faoi róbaí órga

méarlorg an Bhúda

sa ghaineamh . . .

gairdín Zen

chun do cheist a fhreagairt

níl ach bláth amháin

ag teastáil

solas an lae . . .

ní thugann éinne an lampróg

faoi deara

gairdín caonaigh fuaim na báistí ar na búdaí cloch

teampall ina fhothrach -

bloghanna de bhúda

fós ag guí

nach tapa

mar a thagann sé ar ais . . .

dusta

cac gadhair

nó mise . . .

is cuma leis an gcuileog

i mbabhla an mhanaigh

grán ríse amháin

seangán amháin

gaoth gheimhridh -

faid na féasóige

ar an bhfear úd gan dídean

tráthnóna samhraidh seangán ag iarraidh mé a ithe

buaileann clog an teampaill

míle uair . . .

báisteach gheimhridh

deireadh an tsamhraidh . . .

lus na gréine ag dul as

síol i ndiaidh síl

chomh ciúin le teampall sléibhe nead seangán

haiku á scríobh

sa ghaineamh . . .

cuireann tonn bailchríoch air

tráthnóna geimhridh -

líonann scáil mhall

an babhla folamh

an ghrian ar leac na fuinneoige . . .

ní buí níos mó í

an bheach mharbh

fothrach teampaill . . .

caonach ag fás

idir mhéara coise an Bhúda

lán mara an búda gainimh scaipthe ina mhíle tonn

Baile na Síneach -

búdaí stáin ag machnamh

ar sheilf lán deannaigh

searmanas tae -

doirteann an máistir

a aigne sa chupán

gairdín teampaill -

seangáin ag dreapadh suas síos

an cosmas

laistiar den teach tae -

folmhaíonn an máistir

a chupán

2022-02-10

Akiko Yosano (1878–1942)

iompóimidne beirtinár réaltaí, a thaisceidir an dá linnná smaoinigh ar ghuth an fhómhaira chualamar sa leaba

2022-02-09

Little Brickmaker of Bangladesh

|

| Alain Schroeder |

carrying the weightof the world . . .little brickmaker of Bangladeshan Bhanglaidéis . . .ualach an domhain á iomparag déantóir beag brící

2022-02-08

2022-02-07

Tekkan Yosano (1873-1935)

ag caoineadh 'tá sé

ar feadh i bhfad gan náire

gan eolas aige

ar ealaín an dáin ghairid

an ciocáda úd ar ghéag

2022-02-05

John Heartfield

|

tá náire orm ag léamh nuachtán a bhí mé maith dhom é, led' thoil ní léifidh mé arís iad thruaillíos croí is aigne |

|

i am so ashamed i've been reading newspapers please, please forgive me i'll never read one again my heart and mind are sullied |

|

τι ντροπή νιώθω διάβαζα εφημερίδες συγχώρεσέ με δεν τις ξαναδιαβάζω καρδιά και νου μολύνουν Sarah Thilykou a dhein an leagan Gréigise |

2022-02-04

Santoka

fuaim na dtonn

gar dom, i gcéin

cén fhaid atá fágtha agam abhus?

valurile,

cînd departe, cînd aproape;

cît mai am de trăit?

Leagan Rómáinise: Olimpia Iacob

ਲਹਿਰਾਂ ਦਾ ਨਾਦ

ਹੁਣ ਦੂਰ, ਹੁਣ ਨੇੜ;

ਕਿੰਨੀ ਕੀ ਰਹਿ ਗਈ ਮੇਰੀ ਉਮਰ?

Leagan Puinseáibise le Ajmer Rode

2022-02-03

Dakotsu Iida

suaimhneas

an domhan ag dul isteach sa gheimhreadh

súile leath ar oscailt

an domhan ag dul isteach sa gheimhreadh

súile leath ar oscailt

deplin liniștit

intră în iarnă pămîntul

cu ochi întredeschiși

Leagan Rómáinise: Olimpia Iacob

2022-02-02

Eliseu Visconti

| ||

|

chruthaíos thú, a chuid mar a fhoirmítear ceo as gruaim na hoíche saolaíodh tusa chun dul as mo dhánsa bheith i m'fhinné | ||

|

i've created you as mists of morning are formed out of night's despair You were born to disappear my fate to be a witness | ||

|

te-am creat cum ceața se-nfiripă în zori din spaima noapții Ai venit ca să pleci mărturisire mi-e soarta Leagan Rómáinise: Olimpia Iacob |

2022-02-01

Busanna Chív

|

| https://maximdondyuk.com/ |

is there a graveyardbig enough for them all?burnt buses of Kyiv

an bhfuil reilig annatá sách mór dóibh?busanna dóite Chív

Abonnieren

Kommentare (Atom)